Less than four years ago, in 2012 I appeared to be living the kind of life that dreams are made of. I worked as a breakfast show radio presenter at a big commercial station in a beautiful affluent area. I lived in a gorgeous two-bedroomed flat and I owned the little silver jeep that I’d always hankered after. I had plenty of money in my bank account. I had no debt. I could afford sunny holidays and expensive clothes and delicious meals in the nicest restaurants. I had loads of friends, a hot boyfriend and a busy social life.

Food, glorious food

I enjoyed all the perks that a successful media career typically provides; free tickets to everything and complimentary gifts and trips to here, there and everywhere. I constantly had spa days and hotel stays offered to me, free of charge, in the hope that I’d endorse them live on air to our audience of 100,000 people.

I was widely known, well liked, professionally respected, independent and successful. As part of my job I was routinely sent to interview famous people and muck about with my co-host, all in the name of news and entertainment.

I reported live from the VIP areas of the coolest music festivals. Our office threw huge boozy parties all the time. There was always something to celebrate. There most certainly is such a thing as a free lunch if you work in the media industry; I was constantly being wined, dined and headhunted. If I wasn’t being paid to host an extravagant awards ceremony, I was being invited to one as an all-expenses paid guest of honour. I had inadvertently become a local celebrity myself in the area that I lived and worked in. I occupied a public platform that countless people coveted. My opinions suddenly mattered to complete strangers.

Me, presenting another awards ceremony. Whilst everyone else got steadily sloshed, I remained stone cold sober. By that point I felt that once I’d started, I couldn’t stop.

People felt like they knew me before we’d even met because they had listened to me talking, laughing and joking, year after year on the radio, every morning between 6-9am. I never sought after that particular aspect of my job but I soon discovered that it came with the territory whether I liked it or not, and the better I became at broadcasting and the longer I did it, the more my privacy was encroached upon and the less anonymity I had. I started getting fan mail and was often recognised when I went out. I was even followed, photographed and asked for autographs on occasion. It was mostly flattering and funny, but it could be unnerving too. I was once the focus of a sustained hate campaign by one particularly unhinged woman – but more on that another time because that crazy episode deserves its own blog.

Countless people spend their lives desperate for a chance to do the job that I did. I can see why it looked like nothing but fun and games, but it was a high pressure career behind the scenes. It was very early mornings, demanding broadcasting schedules and lots of prior preparation in order for it to appear so effortless. On the surface, I didn’t appear to want for anything. I was getting promotions and pay rises, awards and accolades. I was in demand with countless opportunities. I must be the happiest girl in the world, they wrongly assumed. They were heady times.

Yet, at some point during that summer, I found myself sat with a noose around my neck for an entire day, desperately trying to think of reasons not to end my life.

Using a solid brass hook on the back of my wooden bedroom door, I tied one end of my dressing gown belt to it using a triple knot and I tied the other end tightly around my neck. Then I sat on a stool, with my back against the closed door, in a quiet drunken stupor. A constant stream of tears trickled down my face. I stared blankly at the wall opposite me for hours, balancing the stool on its back two legs, my heart beating steadily. I remember the strange calm that kept washing over me throughout that day, as I weighed up what I perceived to be the pros and cons of life and death. I felt enormous comfort in the knowledge that I could stop the unbearable pain I was in within minutes if I just leaned a little further and fell off the stool.

This wasn’t a cry for help or an empty threat. I was completely alone. Nobody knew where I was or what I was doing that day. Nobody knew just how unreachable I felt. Only I know how close I came to ending my life. Only I know the reasons why I chose to live. There were no witnesses. There were no hysterical pleas or somber warnings. It wasn’t a glib attempt to seek attention or a ploy to emotionally manipulate anybody. And it wasn’t a cry for help. I don’t think I even wanted help. I just so desperately wanted to not feel the way that I felt. I didn’t tell a soul about that day until a long time afterwards.

I was utterly depressed. I felt completely empty. I was spiritually bankrupt and emotionally numb. The way I felt had simply become unbearable, absolutely intolerable and I felt that I just couldn’t go on the same way for a minute longer.

For a good few years leading up to this point, I had grown increasingly worried about my drinking habits. What used to be somewhat unpredictable but mostly manageable, was by now often dangerously out of control. My health had begun to suffer and I found it harder to convince myself that I could stop drinking completely if I wanted to. I could stop for a week or two at a time, maybe three weeks if I really white knuckled it and begrudgingly stayed in, but when I inevitably picked it up again, all bets were off and it took massive amounts of restraint, will power and a careful weaning off period to emerge from one of my binges. By the time I’d fully recovered from a bender, got back on track, made amends for any particularly reckless drunken behaviour I might have got up to on the last binge, it’d be time for another unsuccessful attempt at controlled drinking. It was such a depressing cycle. It had been going on for a long time and was only getting progressively more terrifying.

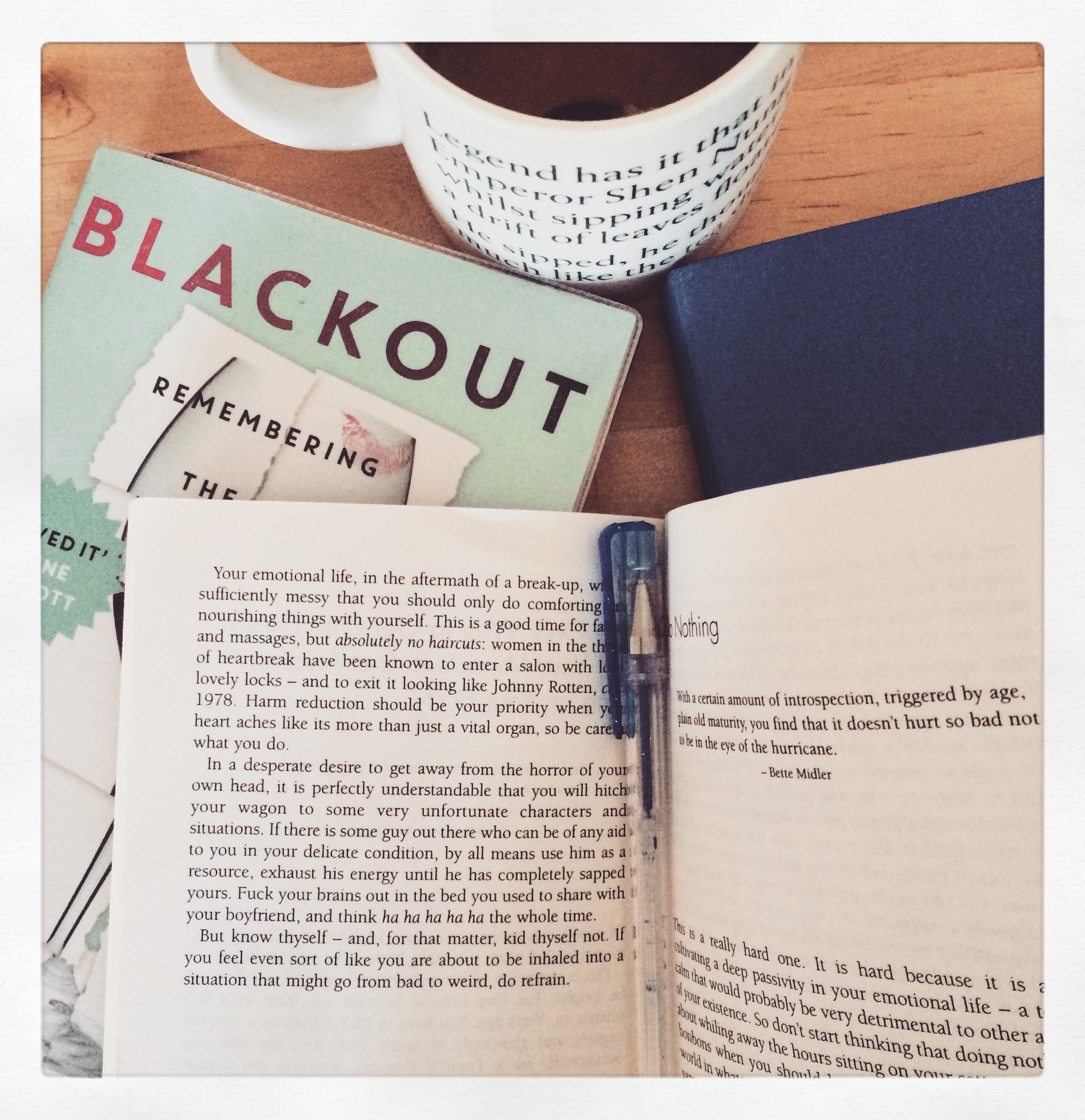

Sarah Hepola beautifully documents her own descent into addiction in her memoir ‘Blackout’

As a result of my drinking and all the unpleasant and unpredictable consequences that went with it, the once promising relationship that I was in at that time was also steadily imploding before my eyes and I was powerless to salvage it. The man I’d fallen in love with understandably didn’t believe my tearful promises anymore and so was slowly but surely turning his back on me and I couldn’t bear it. In response, I did the only thing I knew how to do when faced with such an unacceptable reality; I drank, and obviously, the more I drank, the worse things got and the less able I was to hold things together.

The strange thing about this slow seemingly unstoppable unraveling was that even though at times my performance at work was greatly compromised, I was still really good at my job. I loved certain aspects of presenting and I adored and respected my co-host. I so desperately didn’t want to let him down but looking back I feel I must have done. In many ways that job was a perfect fit for me, but I had arrived at a point where I could barely function and I needed to get out in order to get well. In retrospect, I think that the public performance aspect of being a presenter, inadvertently made me disturbingly skilled at disguising how I really felt. You can’t go live on air and sound exhausted or moody or hungover, you have to learn to hide any negative emotions and appear happy, alert and upbeat. I did it pretty well, but after a while, I was barely holding things together. It was a matter of time before something had to give.

And in fairly quick succession, several things gave way, relentlessly, heartbreakingly and one after the other.

I started either losing things or leaving things at an alarming rate. My health, my family, my boyfriend, my friends, my peace of mind, my job, my financial security, my flat, my jeep, my self-esteem, my motivation for getting out of bed in the morning and finally, my will to live.

Before long, the only thing I felt I really needed was the drug I’d been increasingly relying on. And so I drank to forget, I drank to escape, I drank to relax, there were days when I started drinking as soon as I woke up, and there were nights I couldn’t remember because I was in blackout. I found myself compulsively drinking even though I desperately didn’t want to. I didn’t know how to stop. I didn’t know what to do and I didn’t know anybody I could talk to about it.

I didn’t fully realise it back then, but everything was spiralling out of control and I’d become so depressed and despondent because I had slowly, insidiously, become a slave to my alcohol addiction. I had been effectively committing suicide by instalments over a long period of time and in 2012, after years of progressive alcohol abuse, I had reached the painfully beautiful beginning of the end.